What happens if forest fire ignitions are not suppressed? It’s a tough experiment to perform, but some old Forest Service data may help provide an answer.

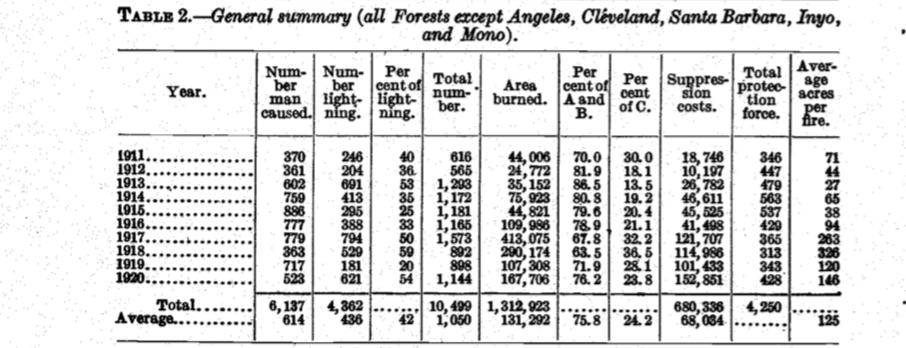

In 1923, the Forest Service published an analysis of fires in 12 California national forests (excepting southern California) that ignited between 1911 and 1920. The data include suppression costs, which are a good proxy for overall suppression efforts.

The “Great Fire” had burned 3 million acres in the Northwest in 1910, ushering in the era of Forest Service fire suppression. Still, in 1911 fire suppression was almost nonexistent. The Forest Service spent $18,746 fighting fires in those 12 national forests that year, which amounts to about $450,000 in today’s dollars.

The Forest Service spent about $500 million fighting fires in California in 2015, and even more than that this year. The numbers show that the agency puts about 1,000 times more effort into fire suppression today than it did in 1911.

Back then, there were no air tankers, no fire engines and few roads leading into national forests. The fires pretty much burned until they went out on their own.

So what happened in 1911? This table has the details. A total of 70 percent of the fires remained smaller than 300 acres. (In the table, “C” fires are those greater than 300 acres, comprising 30 percent of all the fires.)

There are caveats, of course. The early 20th century was unusually wet in California. The climate in western Washington today may be more typical of how the weather was in those parts of California a century ago. Also, a century of logging and fire suppression has altered forest conditions. And there are a whole lot more people living in the region than there was then.

Still, it should come as no surprise that the majority of ignitions led to small fires. In western states, about half of all ignitions are sparked by lightning, which tends to strike where it has struck before, such as oft-burned ridge tops. Those areas serve as natural fuel breaks, limiting the ability of fires to spread.