by Jonathan P. Thompson

In December 2024, President Joe Biden signed the Remediation of Abandoned Hardrock Mines Act into law, opening the door for “good samaritans” to clean up some of the more than 500,000 abandoned mining-related sites across the U.S. without incurring liability if things go wrong. It could help volunteers improve water quality in historic mining areas such as the upper Animas River watershed in southwestern Colorado. But some fear it could also be used to revive mining.

In 1994, the state of Colorado, with the help of a group of local volunteers and mining industry representatives, launched the Animas River Stakeholders Group to study and address pollution from abandoned mines in the upper Animas River watershed. It would be a collaborative approach — without heavy-handed regulations or the dreaded Superfund designation. “We figured we could empower the people in the community to do the job without top-down management,” Bill Simon, one of the group’s founders, told me back in 2016. “Giving the power to the people develops stewardship for the resource, and that’s particularly useful in this day and age.”

Their task was a monumental one: The U.S. Geological Survey has catalogued some 5,400 mine shafts, adits, tunnels, and prospects in the upper Animas watershed, with nearly 400 of them having some impact on water quality. Dozens of abandoned mine adits collectively ooze more than 436,000 pounds of aluminum, cadmium, copper, iron, and zinc into the watershed each year, with waste rock and tailings piles contributing another 80,000 pounds annually. It was here that, in 2015, the Gold King Mine blew out, spewing 3 million gallons of contaminated water into area streams and wreaking havoc for hundreds of miles downstream.

The upper Animas isn’t unusual in this respect. A 2020 Government Accountability Office report estimated that there are more than 100,000 sites in the Western U.S. that pose physical or environmental hazards, ranging from open mine shafts (that can swallow up an unsuspecting human or animal), to contaminated tailings or waste rock piles, to the big one — mine adits discharging heavy metal-laden acid mine drainage into streams.

Federal and state programs exist to address some of these hazards. But the sheer number of problematic sites and the fact that many are on private land make it impossible for these agencies to remediate every abandoned mining site.

For the last few decades, nonprofits and collaborative working groups like the Stakeholders have taken up some of the slack. With funding from federal and state grants and help from mining companies, the Stakeholders removed and capped mine waste dumps, diverted runoff around dumps (and in some cases around mines), used passive water treatment methods on acidic streams, and revegetated mining-impacted areas.

But the most pernicious polluters — the draining adits — were off limits. The volunteer groups couldn’t touch them because to do so would require a water discharge permit under the Clean Water Act, and that would make the Stakeholders liable for any water that continued to drain from the mine — and for anything that might go wrong during or after cleanup. In other words, if some volunteers were trying to remediate the drainage from a mine, and it blew out Gold King-style, the volunteers would be responsible for the damage it inflicted — which could run into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

For the last 25 years, the Animas River Stakeholders, Trout Unlimited, other advocacy groups, and Western lawmakers have pushed for “good samaritan” legislation that would allow third parties to address draining mines without taking on all of the liability. Despite bipartisan support, however, the bills struggled and ultimately perished.

That’s in part due to concerns that bad actors might use the exemptions to shirk liability for mining a historic site. Or that industry-friendly EPA administrators might consider mining companies to be good samaritans. In 2015, Earthworks pointed out that good samaritan legislation wouldn’t address the big problem: A lack of funding to pay the estimated $50 billion cleanup bill. If a volunteer group did trigger a Gold King-like disaster, the taxpayers would likely end up footing the bill.

But last year, Sen. Martin Heinrich, a New Mexico Democrat, and 39 co-sponsors from both parties introduced the Good Samaritan Remediation of Abandoned Hardrock Mines Act, tightened up to alleviate most concerns. It passed the Senate in July of this year, and was sent to the House, where it received support from Republicans and Democrats alike. But the law is far more limited than proponents might have wanted. To begin with, the bill only authorizes 15 pilot projects nationwide, which will be determined via an application process. The proponents will receive special good samaritan cleanup permits and must follow a rigorous set of criteria. No mining activities will be allowed to occur in concert with a good samaritan cleanup.

However, reprocessing of historic waste rock or tailings may be allowed but only in sites on federal land and only if all of the proceeds are used to defray remediation costs or are added to a good samaritan fund established by the act.

In theory, though, a mining company could still use the law to its advantage. Back in the early 2000s, for example, a mining entrepreneur looked to reopen a long-idled mill and use it to reprocess old mine waste dumps as part of the Animas River cleanup efforts. That would have provided an impetus and seed money to get the mill running, which would then be used to facilitate a proposed mining revival in the area. Had a good samaritan law been in effect, the entrepreneur could have used it to shirk liability for de facto mining, so long as it was characterized as remediation.

Similarly, the operators of the White Mesa uranium mill in Utah have proposed cleaning up abandoned mines and reprocessing the waste piles. While this may appear to be an example of today’s “good” mining making amends for yesterday’s “bad” mining, it is in fact merely a way to keep the mill running until the zombified uranium industry is resurrected. It’s analogous to timber companies receiving federal funds to do “forest restoration” and thinning projects — it’s just a more acceptable way to log.

Rep. Frank Pallone, a New Jersey Democrat, raised additional concerns, saying the legislation compromises federal environmental law and “opens the floodgates for bad actors to take advantage of Superfund liability shields and loopholes.” He added that it would give the incoming Trump administration “unilateral power to decide which entities are good samaritans and which are not.”

Of course, the new law only applies to 15 projects — at least for now. While that limits the damage that could be done by bad actors abusing the liability shields, it also limits the benefits, since it can be applied to only a tiny fraction of the abandoned mines that are polluting the region. The Animas River watershed may not benefit at all, since the 48 sites in the Bonita Peak Mining District Superfund site are not eligible for good samaritan remediation.

Now that the liability issue is alleviated, would-be good samaritans will have to figure out how to fund their projects and carry them out effectively. Simply plugging, or bulkheading, a mine adit is costly, difficult, and often futile, because the contaminated water ultimately leaks out into the watershed via natural fractures and faults and through other mines (as was the case with the Gold King). Often, the only solution is active water treatment, which can run into the millions of dollars annually and must be done in perpetuity. Once again, the taxpayers are likely to foot the bill.

The good samaritan law will probably end up benefiting a handful of Western streams. But it does nothing to address the root causes of the problem, which is an antiquated mining law and an industry that has prioritized profit over the environment for well over a century.

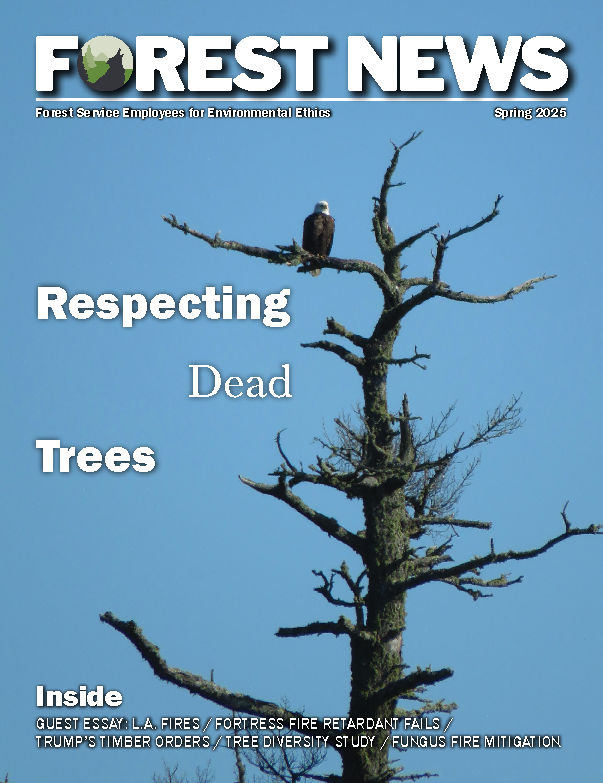

Photo: On the banks of Colorado’s Eagle River, a tributary to the Colorado River, the Eagle Mine sits on private land adjoining the Holy Cross Wilderness Area on the White River National Forest. The site, including the nearby town of Gilman, became part of a 235-acre Superfund cleanup site after it was abandoned due to heavy metals contamination caused by historic mining activities.

Jonathan P. Thompson has been writing about the lands, cultures, and communities of the Western U.S. and the Four Corners Country — his homeland — since the 1980s when he was the editor of the Durango High School newspaper. He went on to work at and own the Silverton Standard and the Miner, a weekly newspaper in a Colorado mining-turned-tourist town. In 2006, he began working for High Country News, first as an associate editor, then editor-in-chief, senior editor, and finally, contributing editor, a role in which he continues today. He is also the editor and founder of the Land Desk, a twice-weekly e-newsletter covering public lands, climate, economies, and cultures of the West. He has authored three books: River of Lost Souls: The Science, Politics, and Greed Behind the Gold King Mine Spill, Behind the Slickrock Curtain, and Sagebrush Empire: How a Remote Utah County Became the Battlefront of American Public Lands.