This summer was exceptionally hot and dry throughout much of the West, and those conditions, unsurprisingly, led to an abundance of wildfires. More than 8.5 million acres have burned across the nation, well above the 10-year annual average of about 5.8 million acres.

As thick smoke settled in the valleys, smothering urbanites, the cries rang out: Something must be done! The “new normal” is unacceptable!

Top Trump administration officials have been happy to lead the charge. Earlier this month, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke sent a memo to his underlings with a blunt message: Make “fuel reduction” a priority. Do everything you can to thin out the woods and thus reduce the chances of “catastrophic” fires.

“This Administration will take a serious turn from the past and will proactively work to prevent forest fires through aggressive and scientific fuels reduction management to save lives, homes, and wildlife habitat,” Zinke said.

Similar statements and directives have come from Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue, who oversees the Forest Service. That agency spent more than $2 billion this year fighting wildfires, a record.

Politicians smelled opportunity. They staged press conferences beneath smoke-filled skies, calling for a return of “active management” of our public forests.

In August, Zinke and Perdue toured a firefighter camp in Montana. They were joined by Rep. Greg Gianforte and Sen. Steve Daines, both Republicans, who left no doubt as to where the responsibility lies for blazes like the Lolo Peak fire, which burned in the background.

“If we don’t address the litigation issue, the frivolous litigation from these extreme environmental groups, we’re never going to get ahead of this curve,” Daines said.

Now that the smoke has cleared, at least for the most part, let’s take a closer look at this call for “active management.”

First, let’s run the numbers. The active management crowd says that more than 50 million acres in the U.S. are at risk of “catastrophic” wildfire and in need of thinning.

That thinning, presumably, would include small-diameter trees as well as shrubs and deadwood. There’s little market for such vegetation. Even when you assume that some of the trees could be sold to timber companies, a conservative estimate is that at least $1,000 would be spent clearing each acre.

You see where this is going. One thousand times 50 million is 50 billion. Are we really prepared to spend $50 billion thinning out the public estate? The Forest Service’s entire budget is about $5 billion.

And, of course, once you thin a stand, you have to keep thinning it. Plants grow back. We suggest a more accurate term for “active management” of this sort: Gardening.

Then there’s the question of efficacy. Does “active management” really make forests more “resilient” to wildfires? Studies have shown that in many forest types, thinning projects actually increase the likelihood of wildfire. More sunlight reaches the forest floor, making the environment hotter and dryer. And the openness allows winds to blow at higher velocities, fanning flames.

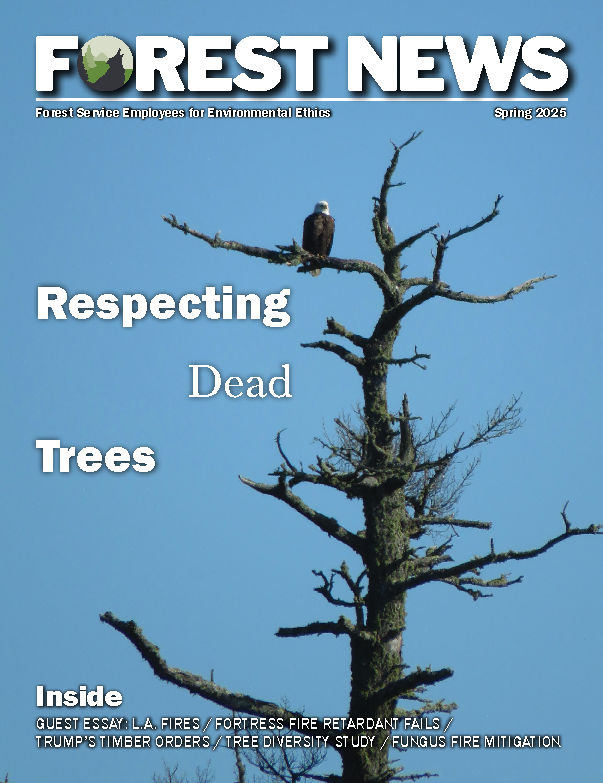

Other recent studies have shown that stands of dead trees—including those killed by insects—are less susceptible to high-intensity wildfire than are live trees, because the dead trees lack highly flammable needles and sap.

It’s telling that Zinke’s recent memo makes no mention of climate change. It also doesn’t mention prescribed burning, which can clear out unnaturally dense stands for a fraction of the price of mechanical thinning.

Nor do administration officials and their allies in Congress have anything to say about the ecological benefits of wildfire. Forests in the West, and the creatures that live there, coevolved with fire. Stands of burned snags are hotspots of biodiversity.

There is, however, a place for thinning in and near our public forests. Clearing out the land in the immediate vicinity of homes and structures, and taking commonsense steps such as clearing leaves and needles out of gutters, does indeed make a difference when a wildfire advances.

In fact, that “defensible space” would be a lovely place to plant a vegetable garden. Even if you’re not an extreme environmentalist.

Thank you for providing another point of view as opposed to the Secretary of the Interior. Zinke fails to mention how he would carry out his intentions as he supports reducing Interior staffing by 4,000 people and supporting the large funding cuts proposed by the administration. He further has announced that 30% of his employees are not loyal to him and the President. I cannot find out how that figure was determined. So much for any respect for his department’s employees. As an Interior employee I thought our loyalty was to the constitution and the rule of law and not to an individual. Not to mention as an employee witnessing the increasing political correctness, intimidation and a lot of various forms of internal rot by those in leadership sweeping through the department. One sees almost daily the deterioration that is underway and unfortunately it has just barely begun. Even a friend of mine that is a counseling psychologist can’t stand to watch the news of what is transpiring. I don’t know how we federal employees will be able to weather this storm with our sanity intact.