Donald Trump’s return to the White House is unprecedented. He’s the first convicted felon to be elected to the presidency after a New York jury found him guilty of 34 charges stemming from a scheme to illegally influence the 2016 election. Manhattan Judge Juan M. Merchan delayed sentencing for the 78-year-old criminal president until Jan. 10, handing down a no-penalty “unconditional discharge,” a rarity for convicted felons.

A grand jury indicted Trump on four charges for his conduct leading up to the Jan. 6 Capitol attack:

- Conspiracy to defraud the United States.

- Conspiracy to obstruct an official proceeding.

- Obstructing an official proceeding.

- Conspiracy against rights (for actions to “oppress, threaten and intimidate” voters).

Controversial decisions by Trump-appointed judges, including Supreme Court justices, enabled delaying tactics and prevented the possibility of more convictions. Additionally, ethics watchdogs documented 3,737 conflicts of interest during Trump’s first term.

During that first term former, Georgia Governor Sonny Perdue served as Secretary of Agriculture. Following Perdue’s nomination to lead the Ag Department and prior to his confirmation, agribusiness corporation Archer-Daniels-Midland (ADM) sold a $5.5-million property to a Perdue-owned business for $250,000, a move widely seen as a bribe. During Perdue’s time in office, the blind trust intended to guard against financial conflicts of interest sold Perdue’s business, including the former ADM property, for $12 million. ADM enjoyed reduced government oversight during Perdue’s tenure.

Perdue named Tony Tooke to lead the Forest Service, but six months later, Tooke stepped down as chief due to allegations of sexual misconduct from earlier in his career. Perdue replaced Tooke with Vicki Christiansen, who served as chief until retiring July 26, 2021, during the Biden administration. Despite an administration riddled with legal and ethical issues, during Trump’s first term, those issues had little, if any, discernible bearing on how the Forest Service and Department of Agriculture operated.

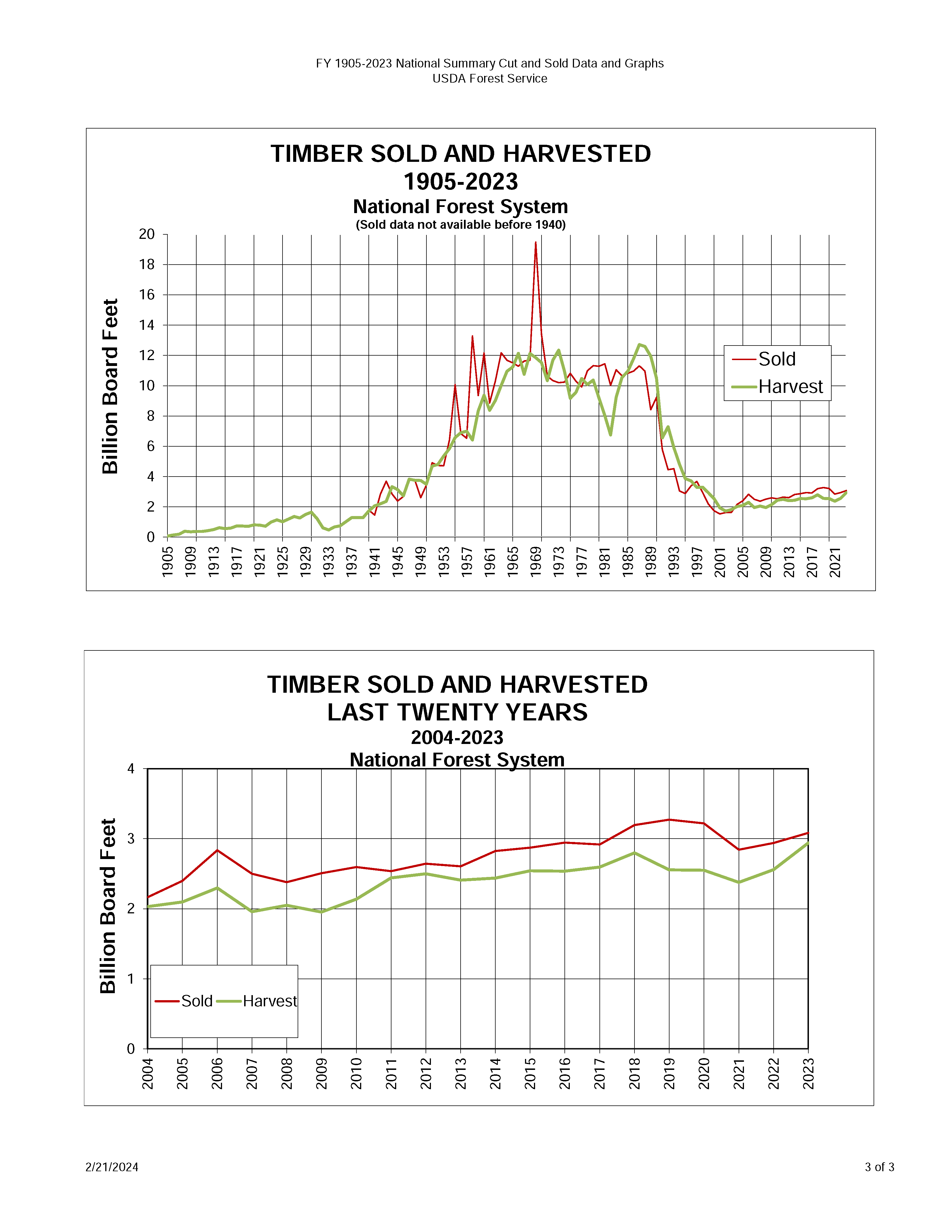

One metric for Forest Service operations is the agency’s “cut-and-sold” reports. These reports show little change in the amount of timber harvested and sold under Trump compared to the Democratic presidents who preceded and followed him. During Barack Obama’s eight years as president, national forest timber sales trended upward from 2.5 billion board-feet per year to more than 2.9 bbf. Timber harvests increased from 1.9 bbf to more than 2.5 bbf. Under Trump, timber sales went from 2.9 bbf to almost 3.3 bbf, while timber harvests peaked at 2.8 bbf before sliding back to Obama-era levels. Biden’s numbers generally landed in between Obama and Trump numbers, but timber harvests under Biden exceeded 2.9 bbf in 2023.

One metric for Forest Service operations is the agency’s “cut-and-sold” reports. These reports show little change in the amount of timber harvested and sold under Trump compared to the Democratic presidents who preceded and followed him. During Barack Obama’s eight years as president, national forest timber sales trended upward from 2.5 billion board-feet per year to more than 2.9 bbf. Timber harvests increased from 1.9 bbf to more than 2.5 bbf. Under Trump, timber sales went from 2.9 bbf to almost 3.3 bbf, while timber harvests peaked at 2.8 bbf before sliding back to Obama-era levels. Biden’s numbers generally landed in between Obama and Trump numbers, but timber harvests under Biden exceeded 2.9 bbf in 2023.

One of the most significant ways presidents wield power is through executive orders, which:

- Determine how legislation will be enforced.

- Decide to what degree legislation will be enforced.

- Implement administration policy and agendas.

During his first term, Trump issued 220 executive orders, an average of 55 per year. One of the more significant Trump executive orders for our national forests was Executive Order 13855: “Promoting Active Management of America’s Forests, Rangelands, and Other Federal Lands to Improve Conditions and Reduce Wildfire Risk.”

The order has been used to justify widespread logging on national forest lands. Perdue’s official statement about the order exploits the wildfire tragedy that ultimately claimed 85 lives in Paradise, California: “As we’ve seen in Paradise Valley, California, wildfire can have devastating lasting effects on our people and our towns. More than 70,000 communities and 46 million homes are at risk of catastrophic wildfires.” Perdue’s statement ignores established facts — Paradise was surrounded by thinned and clear-cut forests and Forest Service researchers have demonstrated that clear-cutting and tree-thinning in our forests provide little, if any, protection for at-risk communities.

For comparison, President Biden has issued 154 executive orders as of this writing, including Executive Order 13990, which rescinded many of Trump’s environmentally-related orders. However, Biden did not rescind Executive Order 13855; throughout Biden’s term, the Forest Service has adhered to Trump’s wildfire risk policies. Trump’s order begins, “It is the policy of the United States to protect people, communities, and watersheds, and to promote healthy and resilient forests, rangelands, and other Federal lands by actively managing them …. For decades, dense trees and undergrowth have amassed in these lands, fueling catastrophic wildfires.”

But as numerous peer-reviewed studies have demonstrated, catastrophic wildfire is driven by wind, regardless of fuel density. And as retired Forest Service Fire Scientist Jack Cohen has proven, community wildfire damage most commonly occurs when wind-blown embers ignite buildings — i.e., protecting people and communities requires minimizing risk in the home ignition zone. Nonetheless, billions of dollars in funding demonstrates that both the Trump and Biden administrations have prioritized logging under the guise of protecting people and communities from wildfire.

Trump’s executive order calls for selling “at least 3.8 billion board feet of timber from USDA FS lands” each year. That timber comes from “treating” more than 6.4 million acres of our national forests to “reduce fuel load.” “Treatment” includes “prescribed burns and mechanical thinning,” but prescribed burning does not increase timber sales. In the years since Trump signed Executive Order 13855, cut-and-sold reports show that timber sales never reached 3.3 bbf, much less 3.8 bbf, under his administration or Biden’s.

Dense, unhealthy forests contain trees with little value beyond the price of a cord of firewood, and firewood permits are not a revenue generator. In fact, efforts to mechanically “reduce fuel loads” cost a few thousand dollars per acre more than the potential revenue from selling the timber, mostly for firewood. Marketing campaigns would have us believe that things like biomass fuel (wood pellets, jet fuel) and biochar (not carbon-negative) are valuable commodities that will help pay for the tree-thinning that politicians claim is needed to protect our communities, but producing these “byproducts” of logging small trees is feasible only with massive infusions of public monies. To actually sell timber without taxpayer subsidies, the Forest Service must turn to healthy, mature and old-growth forests.

Executive Order 13855 also authorizes reviewing “land designations and policies that may limit active forest management and increase the risk of catastrophic wildfires.” This review requirement echoes false claims from industry groups and USDA officials that wilderness designations cause dangerous wildfire conditions by preventing mechanical “treatments.”

Also noteworthy from Trump’s first term is his effort to allow old-growth logging on 9.4 million acres of Southeast Alaska’s Tongass National Forest by removing roadless-rule protections. The Tongass contains the largest intact temperate rainforest in the world, but logging old-growth timber on the Tongass is not profitable. Timber provides less than 1% of southeastern Alaska’s jobs, according to the regional development organization Southeast Conference. By comparison, 8% of regional jobs are in seafood processing, and 17% are in the tourism industry. Both industries would be negatively affected by logging.

Joel Jackson, president of the Organized Village of Kake, responded to Trump’s roadless-rule move in a statement that reads, “We are tied to our lands that our ancestors walked on thousands of years ago. We walk these same lands and the land still provides food security — deer, moose, salmon, berries, our medicines. The old-growth timber plays an important part in keeping all these things coming back year after year; it’s our supermarket year around. And it’s a spiritual place where we go to ground ourselves from time to time.”

Near the end of his first term, Trump also tried to open millions of acres of old-growth forests to logging in the Pacific Northwest by slashing protections for the northern spotted owl. Trump’s move would have decreased protected habitat for the owl by more than a third and was characterized as a “parting gift to the timber industry” by Noah Greenwald, endangered species director for the Center for Biological Diversity.

The Biden administration overturned both of these moves by Trump, marking perhaps the most significant differences between the two administrations regarding Forest Service policy decisions. So while cut-and-sold reports aren’t likely change from Biden’s presidency, Trump could very well succeed at increasing old-growth-logging on the Tongass National Forest and national forests in the Pacific Northwest.

Photo: A forwarder stacks logs on the Flathead National Forest in 2019 as part of a thinning project encouraged by Trump administration policy. This type of heavy equipment in forests has been shown to damage sensitive soils and spread invasive weeds that exacerbate wildfire risk and damage forest health (Forest Service photo).