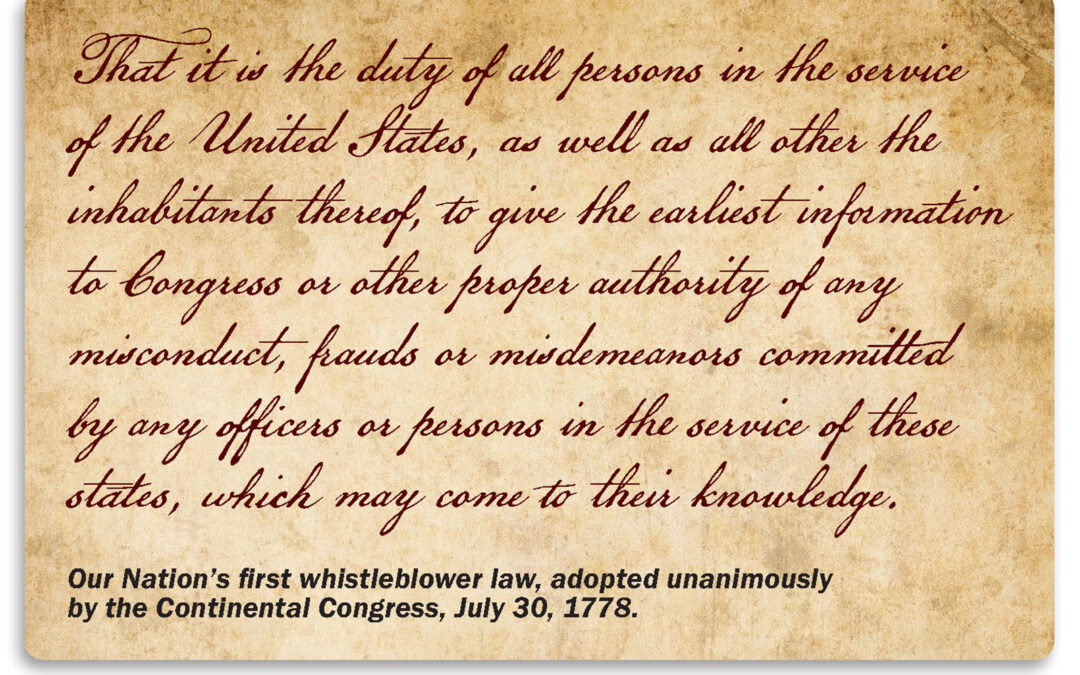

In 1989, Forest Service timber sale planner Jeff DeBonis took the words of the Continental Congress to heart when he penned and distributed an open letter to Forest Service Chief F. Dale Robertson. Jeff called for an end to over-cutting our national forests. “We have a choice,” he explained. “Either meeting the resource management laws like the National Environmental Policy Act and the National Forest Management Act, or getting the cut out. Well, we’ve been trying to get the cut out for 20 years and doing a miserable job on the other end. Let’s try the other mode, let’s quit meeting the cut and start meeting the laws.”

Jeff’s manifesto hit a chord among many of his Forest Service colleagues. After the timber industry called for his termination (which, to its credit, the Forest Service never entertained seriously), Jeff doubled down and founded the Association of Forest Service Employees for Environmental Ethics (“Association” was jettisoned after a New York Times reporter lamented that his editors would cut our good quotes because the organization’s name was too long).

In 1993, on his first day as Forest Service Chief, Jack Ward Thomas seconded Jeff in an email message to all employees asking them to “tell the truth and obey the law.” Ensuring the Forest Service walked Thomas’s fine talk became FSEEE’s seminal mission.

The disconnect between the law and the Forest Service’s on-the-ground behavior was most extreme in the West Coast’s verdant and valuable old-growth forests, especially Alaska’s Tongass National Forest, as forester Mary Dalton was to learn. Mary was a trailblazer — the first of her family to graduate from college and the first woman to lead a timber field crew in the remote Tongass. Her crew was tasked with inventorying the proposed Northwest Baranoff timber sale’s natural resources to determine what harms the sale might cause.

The crew mapped steep, erosion-prone slopes, bald eagle nests, and other concerns. But when the office-based planning team, of which she was not a part, published its draft environmental impact statement, Mary couldn’t find any mention of her crew’s assiduous work. Where the crew found steep slopes, the draft said, “flat ground, no worries.” Where the crew found bald eagles, the draft EIS didn’t voice a peep.

Mary wrote a detailed memo pointing out the draft’s oversights, which she expected to be cured in the final EIS. To her surprise, the final document was unchanged from its draft. In boilerplate, the final EIS noted that those who had commented on the draft could file an administrative appeal to a higher Forest Service officer. She did so.

Unknown to Mary, there was an obscure Forest Service regulation that barred Forest Service employees from appealing its logging decisions. Her appeal was dismissed without a decision, she was given a 30-day suspension for disloyalty, her Tongass position was eliminated, and she had the choice of resigning or relocating to the Mexican border’s Coronado National Forest.

At that point, I learned of her plight and offered FSEEE’s assistance. We brought suit on the grounds that the law on which the regulation was based allows any person who comments to file an appeal. At the hearing, the judge asked the government lawyer one question: “Is it your client’s position that its employees are not people?” The Forest Service capitulated that day and rescinded its illegal regulation. Mary’s record was wiped clean, her pay was restored, and she settled her case on favorable terms. She retired years later after a successful career stewarding national forest land in Alaska, Arizona, and Washington.

Like Mary, Tongass wildlife biologist Glen Ith came face-to-face with the intransigence of his agency’s timber-machine politics. In 2005, Glen sent FSEEE aerial photographs taken by an Alaska Department of Fish and Game employee. The photos showed ongoing logging road construction to access a proposed old-growth timber sale in prime Sitka black-tail deer winter range. What caught Glen’s eye was that the Forest Service had not yet completed the environmental analysis required for the logging, but the agency had already started building the roads. Senator Ted Stevens (R-Alaska) earmarked several million dollars for Tongass roadwork — money that, if not spent by fiscal year’s end, would be lost to the Forest Service, and also incur Stevens’ displeasure. The legally required environmental reviews for the logging and its associated roads were behind schedule, but that didn’t stop the Forest Service from moving forward with spending the road money.

Glen and FSEEE filed suit, challenging the road construction at this and another site we discovered that was suffering the same cart-before-the-horse fate. Glen’s was the first-ever environmental lawsuit brought by a Forest Service employee. We won. The Forest Service retaliated, suspended Glen from work, and eliminated his job. Several days later, Glen passed away from sudden heart failure.

Early on in our roads litigation, Glen told FSEEE that Tongass officials were using irrational numbers in their deer habitat suitability model. He wanted to cure the errors. We agreed the ongoing roads case wasn’t the place to do so, primarily because the issue was not ripe since the timber-sale environmental reviews were not complete at that time.

Glen said he would try to work internally to fix the modeling problem, but he wasn’t confident he would be successful. He believed the errors were intentionally designed to allow the Forest Service to defend logging high-value old-growth forest habitat. Glen assiduously documented the problems with the deer habitat model — documents that Greenpeace’s Larry Edwards later found in the administrative record. In 2011, in a 3-0 opinion, a federal appeals court ruled that the Forest Service’s use of its deer habitat model was “arbitrary and capricious” because key numbers in the model were altered without any rational explanation.

DeBonis, Dalton, and Ith exemplify the best our civil service provides to the American public. When forced to choose between loyalty to the Forest Service’s mission — telling the truth and obeying the law — versus getting along and going along, they chose allegiance to the mission. They did their jobs.