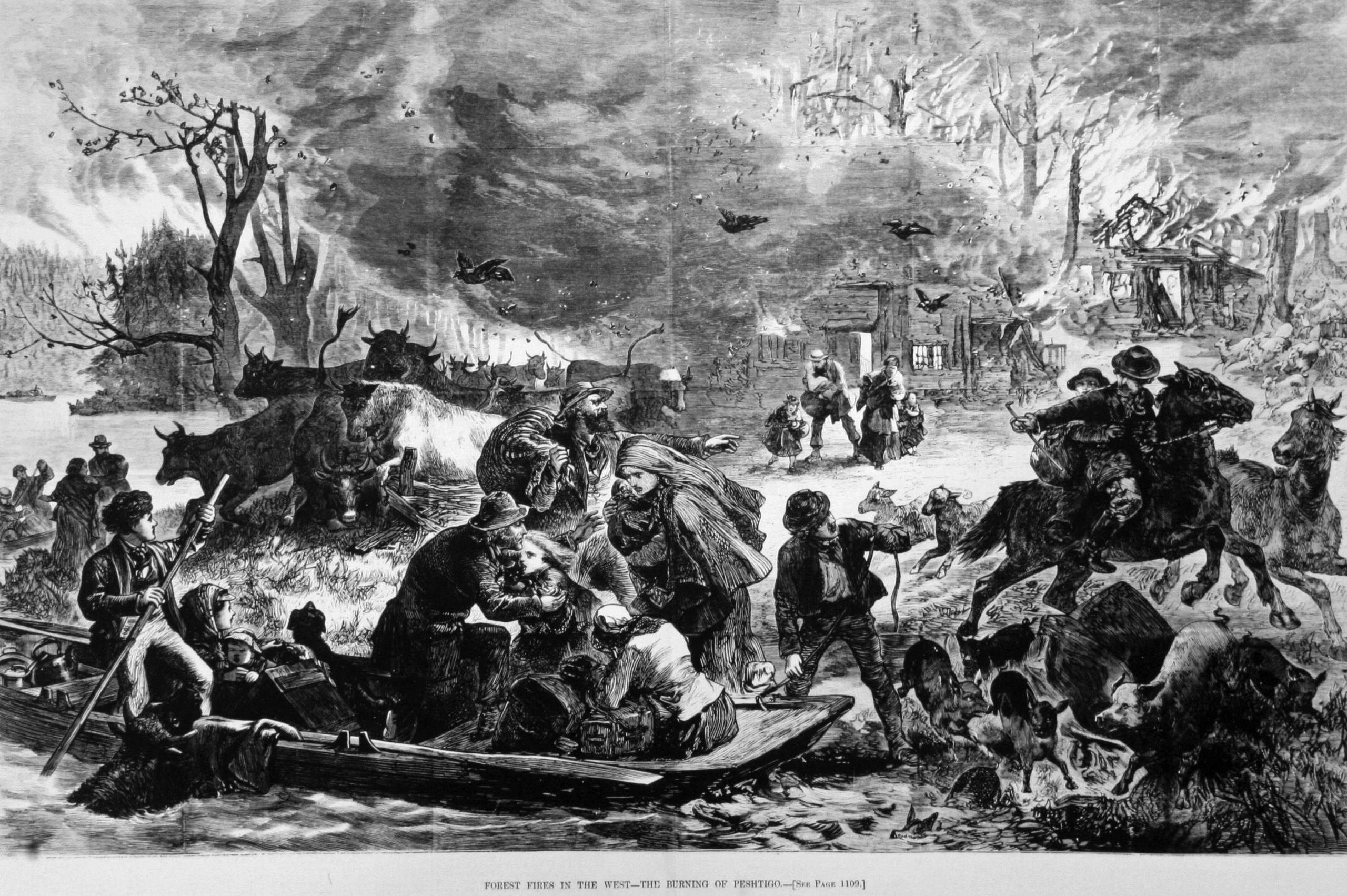

On the night of October 8, 1871, in Peshtigo, Wisconsin, “all hell rode into town on the back of a wind.” In two hours, the Peshtigo Fire decimated a swath of forest 10 miles wide by 40 miles long and obliterated the towns of Peshtigo and Brussels in northeastern Wisconsin. According to the Peshtigo Fire Museum, the conflagration ultimately burned 1.3 million acres, destroyed 17 towns, and killed as many as 2,500 people. In spite of uncertainty about the exact number of lives lost in the fire, it remains the deadliest fire in U.S. history.

Before settlers arrived, the entire northern half of Wisconsin was covered by forest. Many of the trees were hundreds of years old. Pine trees grew to heights of 120 feet with 3-foot diameters. By 1871, Peshtigo had become the principal settlement in the region, and timber fueled the town’s economic engine. The woodenware factory in Peshtigo was the largest in the world. The sawmill was one of the largest in the U.S. Both were built by William Ogden, former mayor of Chicago, who bought thousands of acres of Wisconsin forest, established a barge line between Peshtigo and Chicago, and fostered construction of railways to bring lumber to his sawmill.

The timber industry played a leading role in setting the stage for the firestorm. Lumberjacks would clear an area and set fire to the remaining debris or leave piles of woody fuel to dry into tinder. Farmers also set fires to clear their fields or moved in after the land was cleared by loggers, burning stumps to prepare for plowing. Railroad crews set fires to clear debris, and coal-fired steam engines spewed sparks and cinders from their smokestacks. Many of the fires were left to die out on their own, often burning underground, fed by tree roots and peat, so fires were common around Peshtigo at the time.

A period illustration of the Peshtigo Fire.

The fall and winter of 1870 were dry, followed by an even drier spring. The summer of 1871 was one of the driest on record. Local tribes couldn’t use canoes to gather wild rice in the dry marshes. River flows were so diminished that logs couldn’t be transported and remained stacked on the river banks, awaiting rain.

Peshtigo was already a tinderbox. Almost all of the buildings in the town were made of wood, from floor joists to shingles. Firewood was stacked next to houses for winter. Wooden boardwalks served as sidewalks. Roads leading in and out of town were surfaced with split logs. Streets were paved with wood chips, and mattresses were stuffed with sawdust.

When Oct. 8 arrived, small fires were already burning in the forest. By 10 p.m., a change in the weather sealed the fate of Peshtigo. A massive low-pressure cell moved in from the west, bringing high winds that whipped up the flames of the small fires until they merged into the historic conflagration. A column of hot air rising above the fire produced stronger winds in a vicious cycle that led to hurricane-force gales, creating a literal firestorm with winds in excess of 100 mph.

Father Peter Pernin survived the fire by spending over five hours in the frigid Peshtigo River, where some died of hypothermia. That night he first noticed, “above the dense cloud of smoke over-hanging the earth, a vivid red reflection of immense extent,” followed by “a distant roaring, yet muffled sound.” The sound “grew into a roar … like a freight train or huge rushing waterfall. Suddenly, big sheets of flame blew out of the forest. Everything in the fire’s path was instantly consumed. … High winds blew people to the ground, and the hot air burned people’s lungs. Dust and smoke blinded them as they ran for shelter or to the river.”

The Peshtigo disaster prompted the federal government to adopt new forest management programs, convinced in part by early conservationists like Franklin Hough and Bernhard Fernow, who cited the Peshtigo Fire to support their argument that forest fires threatened commercial timber supplies. By 1876, Congress had created the office of Special Agent in the Department of Agriculture to assess the quality and conditions of U.S. forests. In 1881, the office was expanded into the Division of Forestry.

Hough became its first chief, and Fernow was the third person to lead the division, laying the groundwork for establishment of the Forest Service. In 1889, the Santiago Canyon Fire burned more than 300,000 acres in Southern California, and by 1891, Congress passed the Forest Reserve Act to protect timber supplies and watersheds.

The legislation authorized the President to designate forest reserves on public lands, which were managed by the Department of the Interior until 1905, when President Teddy Roosevelt placed the reserves under the management of the Department of Agriculture’s new Forest Service. Just five years later, a series of forest fires known as The Big Blowup burned 3 million acres in Montana, Idaho, and Washington. Forest Service officials convinced themselves that, with sufficient men and equipment, they could have prevented the devastation of these fires.

The Big Blowup of 1910 created a wildfire ‘‘hurricane” near Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, similar to conditions reported by survivors of the Peshtigo Fire.

They also convinced a worried nation that only total fire suppression — carried out by the Forest Service — could prevent catastrophic wildfires. From 1920 to 1938, William Greeley, Robert Stuart, and Ferdinand Silcox served as successive Forest Service chiefs. All three men had fought the 1910 fires, and all three maintained a policy of total fire suppression. They even opposed “light burning,” which was favored by many ranchers, farmers and timber managers, who recognized the practice as beneficial. But for the Forest Service leadership, all fire was bad because it destroyed timber. The “Big Blowup” of 1910 cemented for a century the policies that the Peshtigo Fire had first inspired.

This fire-suppression policy led to construction of fire protection infrastructure, including forest road networks that contributed to fracturing wilderness. The Forest Service leaders also promoted the Weeks Act. Its passage in 1911 empowered the agency to provide financial incentives for states to fight fires, ensuring a dominant Forest Service role in directing fire policy across the country. Over the ensuing decades, fire suppression efforts incorporated new technologies and techniques — airplanes, smokejumpers, fire retardants — and demanded ever larger budgets for land managers obsessed with suppressing fires.

During the 1960s, scientific research began to show that fire played a critical role in forest ecology, and that research eventually led to changes in Forest Service policy. The agency began to allow natural-caused fires to burn in wilderness areas. As the “let-burn” policy took shape, the Forest Service began to recognize the need for prescribed fire to maintain forest health and resilience. But agency missteps and larger fires in recent years have generated pushback from a populace with legitimate concerns and perhaps convinced by past “wildfire education” efforts that all fire is bad. Increasing residential sprawl into the “wildland-urban interface” has also complicated fire issues, putting more lives and property in more areas where ecosystem health depends on fire.

The Peshtigo Fire is still studied as an example of bad forestry practices and the power of catastrophic wildfire. The fire did help to inspire better natural resource management, including less wasteful timber-harvesting techniques, as well as today’s conservation and environmental principals. Ultimately, the historical thread that started with the Peshtigo Fire leads to today’s Forest Service firefighting efforts, which represent more than half of the agency’s entire budget. And this deeply ingrained commitment to fire suppression limits funds available for the kinds of land-management activities that can help restore forest health and prevent catastrophic wildfires.