by Andy Kerr

As public lands conservationists continue their fight to save the last of the mature and old-growth forests for the benefit of this and future generations, we must not forget the preforests.

In 1988, fires in Yellowstone National Park caused the media to declare that the entire park was “destroyed.” Today, people still flock to the world’s first national park. While the forests of Yellowstone have changed, they are still magnificent.

In 2020, much old-growth forest in and around the Opal Creek Wilderness and the surrounding Opal Creek Scenic Recreation Area burned in the Beachie Fire, one of several fires burning at the same time in the North Santiam Canyon in Oregon. Some — but not all — of the forest burned at a high severity, what ecologists refer to as a stand-replacing event. In such an event, most — but usually not all — of the live trees are burned. Most — but not all — of those trees die.

I, and many others, worked for decades to save Opal Creek from chainsaws and bulldozers. We were finally successful in 1996. I’m not hankering to go back to see Opal Creek because I know I will feel sad to see the loss of so much old-growth forest that I knew. Those feelings of personal loss will be real, but they will also be irrational.

A forest stand never just stands there. Even an old-growth forest that has stood for centuries is a forest constantly moving through forest succession, though it is often so slow as to be imperceptible to humans. Plots monitored for an extended period of time show ecologists the inexorable march of change.

Occasionally, a catastrophic event dramatically resets natural forest succession, and an old-growth forest ceases to be a forest. While “catastrophic,” this rapid reset is never a catastrophe (“an event causing great and often sudden damage or suffering; a disaster”) for the forest. In the long run, ecological resets are as desirable as they are inevitable.

But in our current culture, such resets are often misunderstood and consequently mismanaged. A 2014 paper by Swanson, et al., asserts, “Traditionally overlooked by foresters as unproductive and ecologists as disorganized, naturally regenerating forests in the Pacific Northwest are perhaps the least understood forest condition in the region.”

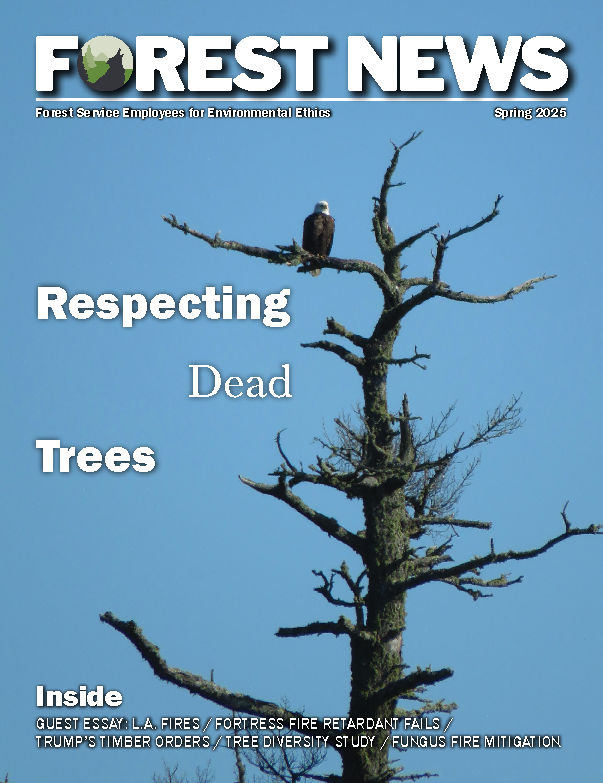

A classic complex (undisturbed) preforest resulting from fire in Yellowstone National Park (photo by Damiel Mayer).

The Ecological Role of Preforests

In their classic scientific paper (“The Forgotten Stage of Forest Succession: Early-Successional Ecosystems on Forest Sites,” 2010), Swanson, et al., define early successional forest ecosystems as “those ecosystems that occupy potentially forested sites in time and space between a stand-replacement disturbance and re-establishment of a closed forest canopy. These ecosystems undergo compositional and structural changes (succession) during their occupancy of a site.”

Scientists, foresters, and others have given these ecosystems many names, including preforest, early seral forest, early successional forest, stand initiation stage, reorganization phase, establishment phase, snag forest, etc.

An old classic forestry textbook from 1990, Forest Stand Dynamics, labeled this stage as stand initiation, the clear implication being that the only purpose of this stage of forest succession is to get stand growth going so that some good (rhymes with wood) can come from the forest again. A new classic forestry textbook from 2018, Ecological Forest Management, labels it the preforest stage and recognizes, describes, and honors its ecological and social values.

The authors of Ecological Forest Management explain why they call it the preforest stage: “The absence of significant tree dominance of the site in the Preforest Stage (PFS) allows other plant life forms to flourish and new cohorts of trees, particularly shade-intolerant species, to become established…. The most fundamental feature of the PFS is that trees are not the dominant plant life form. Labeling this stage as preforest clearly identifies it as a non-tree-dominated ecosystem but one that is occupying sites that will eventually become forests….

“[Some] other labels applied to this stage … focus attention on regeneration of that new cohort of trees and, therefore, have a tree-centric bias. In fact, tree regeneration is only one of the many important processes that occur in the PFS, and those other labels ignore more of the unique ecological roles of the PFS, which are actually a consequence of the absence of tree dominance.”

The book treats preforests as one of the four important stages of forest succession, along with young forest, mature forest, and old-growth forest. While ecologically significant lines can be drawn to demarcate the stages, in reality it’s one long circular continuum.

Growing trees use a lot of nitrogen from the soil. Preforest is the stage in forest succession where the most nitrogen is captured from the air and returned to the forest through an abundance of nitrogen-fixing plants. Old-growth forests, because they live so long, have come to rely on nitrogen-fixing lichens in the canopy that fall to the ground and recharge the soil.

Preforests are the rarest forest stage. Before the European invasion, forests that were naturally regenerating after a stand-replacing event occupied between 5% and 20% of the land in the American West at any particular time. Today, early successional forest ecosystems are even more rare and limited in extent than old-growth forests. Compared to the 19th and early 20th centuries, the extent of preforests in Oregon’s Coast Range and Cascades has been reduced by more than 50%. It’s similar in the Northern Rockies.

One reason preforest is undervalued is that it has the shortest duration of any forest stage. It also has the least amount (in number and size) of trees of any stage. Since preforest follows a stand-replacing event, far fewer trees are standing, and they are not standing particularly tall. In the American West, preforests can naturally last 10-50 years — if not interrupted by humans, which they most often are. The longer the duration of the preforest stage, generally the more species richness is found there.

When Swanson, et al., published “The Forgotten Stage of Forest Succession: Early-Successional Ecosystems on Forest Sites,” it was as influential in my thinking about and understanding of forests as was the Forest Service technical report Ecological Characteristics of Old-Growth Douglas-fir Forests (Franklin, et al., 1981). In their own ways, both papers called bullshit (a precise term of ecology) on the conventional forestry “wisdom” that both of these stages of forest succession are devoid of ecological or societal value. (I hope to soon see a paper with the title “Ecological Characteristics of the Ignored Stage of Forest Succession: Mature Forests.”)

Swanson, et al., tell us, briefly:

- Naturally occurring, early-successional ecosystems on forest sites have distinctive characteristics, including high species diversity, as well as complex food webs and ecosystem processes.

- This high species diversity is made up of survivors, opportunists, and habitat specialists that require the distinctive conditions present there.

- Organic structures, such as live and dead trees, create habitat for surviving and colonizing organisms on many types of recently disturbed sites.

They then go on to say something that points toward managing preforests to ensure that their ecological value accrues to the benefit of this and future generations:

Traditional forestry activities (e.g. clearcutting or post-disturbance logging) reduce the species richness and key ecological processes associated with early-successional ecosystems; other activities, such as tree planting, can limit the duration (e.g. by plantation establishment) of this important successional stage.

Andy Kerr is the czar of The Larch Company (www.andykerr.net) and consults on environmental and conservation issues. The Larch Company is a for-profit non-membership conservation organization that represents the interests of humans yet born and species that cannot talk.