They are wilderness areas without a capital “W.”

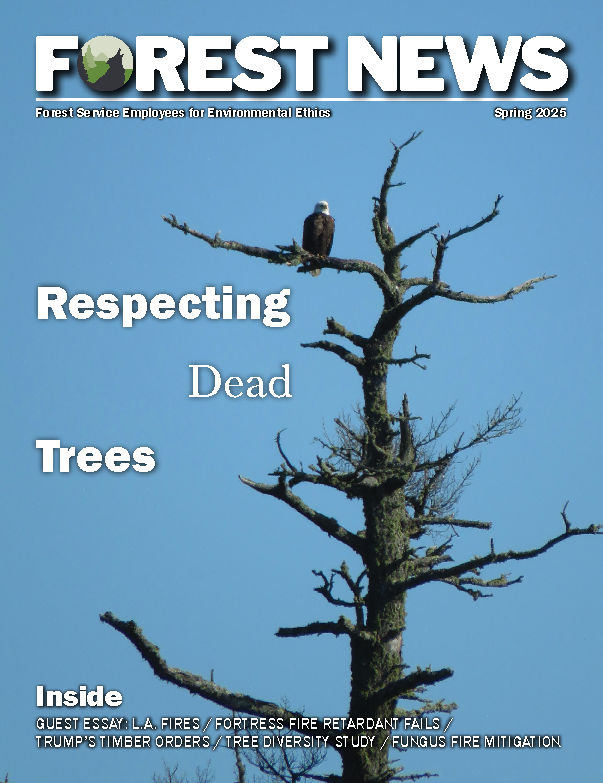

The Tongass National Forest is the largest in the United States. U.S. Forest Service photo.

They are “inventoried roadless areas,” governed by a rule adopted in the waning days of the Clinton administration designed to preserve the last remaining stretches of national forests that roads had not yet pierced. While they lack the formal protection afforded by the Wilderness Act of 1964, the 58.5 million acres of designated roadless areas possess many of the same attributes—primeval forests, stunning mountain scenery, wild rivers and streams, rich wildlife habitat.

Now, however, the largest single component of the roadless system is under threat.

In August, Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue announced that the Trump administration would develop a new roadless rule for Alaska’s Tongass National Forest. Currently, more than half of the Tongass—9.5 million acres—is protected from logging and road-building under the 2001 rule.

Administration officials have made no secret that the revision process is being driven by a desire to open more of the Tongass to logging and other industrial activities—something that Alaska state officials have lobbied for ever since the roadless rule was adopted.

“The national forests in Alaska should be working forests for all industries,” Perdue said in announcing the start of the rule-making process.

Conservationists contend that opening up the Tongass to logging and road-building would usher in a return to the bad old days of conflict and controversy on the Tongass, which includes the largest stretch of temperate rainforest left on the planet.

“The Trump administration’s decision to appease the State of Alaska and walk away from protections for roadless areas and old-growth habitat in the Tongass National Forest is devastating news for Tongass wildlife that rely on intact forests and watersheds,” said Jamie Rappaport Clark, president of Defenders of Wildlife.

An Alaska-specific roadless rule could also jeopardize a recently announced policy that calls for phasing out the logging of old-growth forests on the Tongass.

And, critics say, withdrawing roadless protections from the Tongass would fly in the face of new economic realities in Southeast Alaska. The timber industry, boosted by massive government subsidies, may have been King of the Tongass during the go-go logging days of yesteryear.

But timber no longer rules the roost in Southeast Alaska. In fact, it’s not even close.

•••

In 2016, for the first time ever, tourism took the top spot in Southeast Alaska’s economy, nudging out the seafood industry in terms of both jobs and wages.

The “visitor industry,” as it is labeled in the annual Southeast Alaska by the Numbers economic report, generated nearly $230 million in earnings that year and accounted for 7,752 jobs. That topped the seafood industry, which generated about $210 million in worker earnings and accounted for 3,854 jobs. (All private industry sectors in Southeast Alaska are dwarfed by the public sector, which in 2016 generated more than $770 million in earnings and supported 13,052 jobs.)

Of the 13 industries tracked in the report, timber came in dead last, accounting for total earnings of about $16 million and 313 jobs. The timber industry has all but disappeared from Southeast Alaska, with harvest levels down 96 percent since the peak in 1991.

Sealaska, a Native corporation, owns more than 300,000 acres in Southeast Alaska and is the top timber producer in the region. Viking Lumber, on Prince of Wales Island, owns the last remaining mid-sized mill in the region.

While supporters of the timber industry regularly blame lawsuits brought by environmental groups for the lack of logging, the real reason comes down to simple economics: logging in the rugged, remote Tongass National Forest doesn’t pencil out. One of the main reasons why is the high cost of building logging roads. The Southeast Alaska by the Numbers report puts it succinctly: “Timber available for sale is often uneconomic, thereby constraining supplies to mills.”

The region’s visitor industry, meanwhile, is booming. In 2016, 1.5 million people visited Southeast Alaska. More than 1 million of those arrived by cruise ship. Those numbers are expected to continue to rise in coming years.

Those who oppose rescinding protections for roadless areas on the Tongass point out that the people who visit the region don’t travel there to see clearcuts and logging roads slashing through the rainforest. They come for the pristine scenery and the chance to catch glimpses of a wealth of wildlife—bears and wolves, otters and whales—in a natural setting.

Despite these economic realities, Alaska’s congressional delegation remains steadfast in its insistence that the Southeast Alaska timber industry can be resurrected.

Senators Lisa Murkowski and Dan Sullivan, as well as Rep. Don Young, are unanimous in their praise of the Trump administration’s decision to overhaul the roadless rule for Alaska. On the day the revision plan was announced, they released a written statement. Said Murkowski:

“As I have said many times before, the Roadless Rule has never made sense in Alaska. I welcome today’s announcement, which will help put us on a path to ensure the Tongass is once again a working forest and a multiple use forest for all who live in southeast.”

What’s behind the seemingly unshakeable support of Alaska elected officials for a timber industry that has dwindled to next to nothing in the state?

Hunter McIntosh is president of The Boat Company, a nonprofit organization that offers educational boat tours in the waters of the Tongass. He’s been leading tours in Southeast Alaska for nearly four decades. Support for extractive industries—including logging—is simply part of Alaska’s DNA, he says.

“I think the disconnect comes from a deep-seated belief by elected officials in Alaska that the only way they can bring in revenue is through extraction of natural resources,” McIntosh says. “It’s how the state was founded—with the Gold Rush. It just evolved from there.”

•••

The roadless rule revision pro-cess promises to be controversial. By all accounts, the Trump administration also wants it to be quick—at least when compared to standard timelines for major land management initiatives on public land.

On Wednesday, the Forest Service will hold the last in a series of “public information meetings” regarding the roadless rule revision. After that, the agency will develop an environmental impact statement that looks at options for a new rule.

The agency intends to adopt the new rule by June 2020—before the end of Trump’s first term.

The revision comes shortly after an exhaustive, multiyear effort to amend the Tongass National Forest’s management plan. In addition to phasing out old-growth logging, that plan also assumes that the Tongass would be subject to the full protections afforded by the 2001 roadless rule—that those 9.5 million acres would remain off limits to road construction for logging.

If Perdue, who has final say on the rule, adopts a version that allows for road-building, the Tongass land management plan may well have to be amended again. That prospect doesn’t sit well with those who devoted huge amounts of time and energy crafting the current plan—or with conservationists.

“My reading of it is that if the roadless rule went away in the Tongass, the management plan itself would still hold sway over the roadless areas,” says Susan Culliney, policy director for Alaska Audubon. “But that’s the concern—that we would get that one-two punch of the roadless rule redacted and the management plan amended.”

Forest Service officials say they do not yet know if another plan revision will be needed.

“Right now, we are not looking at a plan amendment,” said Dru Fenster, a public affairs specialist for the Forest Service’s Alaska region, in an email response to questions. “When the rule is finalized in June of 2020, it may require us to do a plan amendment, depending on if there are changes in the rule.”

In public, at least, the agency promises to strike a balance with the new rule. The agency’s website for the Alaska region says that the new rule will “further Alaska’s economic development, and other needs, while also conserving roadless areas for future generations.”

Despite such seemingly reassuring language, McIntosh of The Boat Company remains skeptical. Even with the roadless rule in effect, a quick perusal of the Tongass’s budget shows that the Forest Service spends much more money on timber than on, say, administering special-use permits for tour and recreation organizations.

“Those funds go to timber sales and developing environmental impact statements and organizing meetings that go nowhere,” he says. “Not to assisting industries that actually bring in money to the Forest Service and the state.”