Pacific Crest Trail thru-hikers had better be ready for a lot of detours in Oregon this summer. In November and December, after fire season-ending rain and snowstorms, the Forest Service issued orders closing three of Oregon’s most popular trail segments (including Three Sisters and Mt. Jefferson), along with their associated wilderness areas and connecting trails. The reason? “Public Safety.”

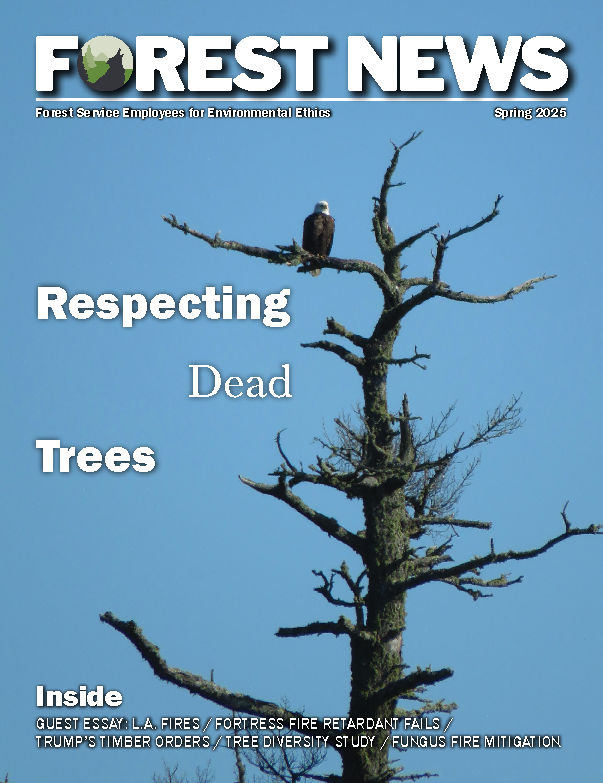

This summer, fires burned parts of the wilderness areas that have been closed to the public. As with most western Oregon fires, the aftermath shows a patchy mosaic of burn intensities. Ridge tops tended to burn hotter; valley bottoms cooler; many acres not at all. Fires are not uncommon in these Douglas-fir/western hemlock forests, with a return interval on the order of 100 years. The popular French Pete trail passes through forests with numerous fire-scarred trees, snags killed by previous fires, and other fire-affected structure typical of the area’s old-growth forests. This trail, like dozens of others, is now closed to the public.

The Wilderness Act directs the Forest Service to manage wilderness areas for “their primeval character and influence” to “preserve natural conditions.” Wilderness areas are to be “affected primarily by the forces of nature” and “offer primitive and an unconfined type of recreation.” The Act’s only reference to safety is an exception to the ban on motorized equipment if “required in emergencies involving the health and safety of persons within the area.”

Even if the Wilderness Act countenanced a nanny state approach to wilderness management, the Forest Service did not explain its closure decisions, nor invite public comment on whether it’s too dangerous to hike in these woods. People do die in wilderness areas. They drown, freeze, fall off mountains, and have heart attacks. Falling trees cause about one percent of wilderness-related fatalities.

The default status of national forests is that they are open, by law and without permit, to dispersed recreation. The Forest Service must follow the law when it decides to lock the public out. Under the Administrative Procedures Act, the Forest Service must explain its reasons, including how the facts support its conclusions. The Forest Service did not do so. The agency must also follow procedures outlined in the National Environmental Policy Act, including explaining the degree to which its closure decision affects “extraordinary circumstances,” which would include wilderness areas. The orders have obvious and profound effects on wilderness and Pacific Crest Trail users, eliminating all forms of dispersed recreation. The Forest Service made no attempt to comply with NEPA.

Insofar as it offers any explanation at all for the closures, the Forest Service cites hazards posed by falling trees and snags.

All trees fall down. Some fall when they are alive. Some fall after they die. Some fall when they are young. Some fall when they are old. Wind knocks trees over. Trees fall over from root decay. Trees also fall after being burned in forest fires.

Wait a second … go back and click on that last link—the one about trees falling over after forest fires. Most of the lodgepole pine trees in that photo look like they’re still standing. And they’ve been standing long enough for the aspen in the understory to sprout and grow.

So how long does a tree stand after being killed by fire? It’s an area of research almost wholly neglected by so-called tree hazard evaluations. Ecologists, however, have studied snag persistence to assess wildlife habitat.

In a western Idaho study, for example, 95 percent of Douglas-fir snags were still standing four years after fire. More than 80 percent remained upright 11 years later.

If the Forest Service thinks wilderness should remain closed until the fire-killed trees have fallen over of their own accord, they’ll have to lock the public out for years. Or the Forest Service could treat wilderness trails as it does roads and cut the potentially hazardous trees, if doing so “preserves its wilderness character.” Or the Forest Service could do as it has in Idaho—open the wilderness and warn visitors that they are responsible for taking reasonable precautions to ensure their own safety.

We have lost too much wilderness already. Lets stop closing wilderness off to people and lets have our wilderness remain open to everyone. We can clear dangerous and fallen trees away from the Pacific Crest trial.