After FSEEE won a preliminary injunction to halt the Willamette National Forest Danger Tree Reduction Project, the U.S. Forest Service has decided to withdraw the project. We’re sending out a big “Thank you!” to all of you who made donations to help us win this round.

The project would have removed so-called “hazard trees” within 200 feet of 404 miles of roads where fires burned in 2020. In granting the injunction, Judge Michael McShane ruled that the Forest Service had illegally skirted a National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review before approving the project.

As we said in our July member letter, your contributions have supported our lawsuit against this illegal timber harvest as well as our efforts to reopen tens of thousands of National Forest acres that the Forest Service has closed, and the two issues are intertwined. The Forest Service claims that the trees killed or even just scorched by the fires pose a dire threat to the public and need to be removed so that they don’t fall on people. In the meantime, forest and wilderness lands in and around burned areas are closed to protect “public safety.”

So if you want to hike the Pacific Crest Trail, it’s now impossible to follow the entire path without risking a $5,000 fine and 6 months in jail. The same goes for Jefferson Park, one of Oregon’s most popular backpacking destinations. Northern California’s Middle Fork of the Feather River, a National Wild and Scenic River, is also closed to the public because a forest fire burned nearby.

According to Dr. Travis Heggie, former public risk management specialist for the National Park Service, “Across all federal lands in the United States, 1% of fatalities suffered by the visiting public are caused by falling trees,” while 40% of backcountry deaths result from people falling.

For over 100 years, the Forest Service has ignored this “mortal threat” from dead trees, so what changed?

The three states where the Forest Service is acting most vigorously to protect the public from dead trees just happen to be where National Forest logging levels have dropped the most — by 90 percent — in the last 30 years. Until the early ’90s, Washington, Oregon, and California led the country in national forest logging, accounting for more than half the timber harvested from national forest lands.

The billions paid for those logs padded the Forest Service budget, as the agency is one of the only in the federal government that gets to keep for itself the money paid for the public’s assets — i.e., our trees. After federal judges ordered the Forest Service to follow the law in the ’80s, logging levels to plummeted, which dried up the Forest Service slush fund.

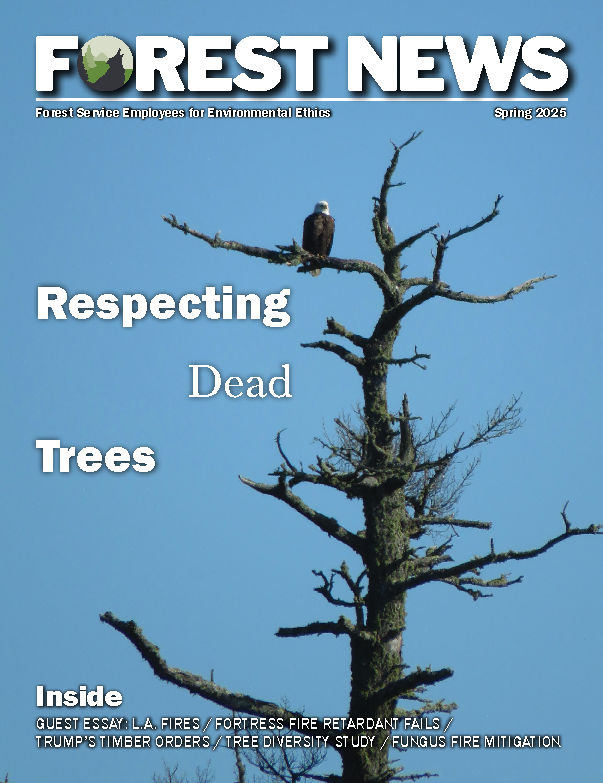

The Forest Service quickly pivoted. If it couldn’t sell timber from green, unburned forests, maybe it could get away with selling the timber after forest fires. “Salvage logging” became the new Forest Service mantra. “If we don’t cut trees after fires, the wood will go to waste,” the Forest Service asserted. Once again those pesky environmental laws got in the way. Those big dead trees the Forest Service and its timber industry clients coveted are also the most ecologically important trees in our National Forests.

Together, we won this round and saved thousands of acres of critical habitat. Together, we’ll continue to press forward until the Forest Service reopens our public lands.

Again, thank you for your support!