A federal judge agreed with FSEEE, blocking most of a Willamette National Forest commercial logging project that would affect habitat for the northern spotted owl, which is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

In the Nov. 5 order granting the preliminary injunction, U.S. District Judge Michael McShane ruled that the Forest Service illegally skirted a National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review before approving the project.

The project would remove so-called “hazard trees” within 200 feet of 404 miles of roads where the Lionshead, Beachie Creek and Holiday Farm fires burned in 2020. The Forest Service claims the trees need to be removed in order to reopen forest and wilderness lands that have been closed since September 2020.

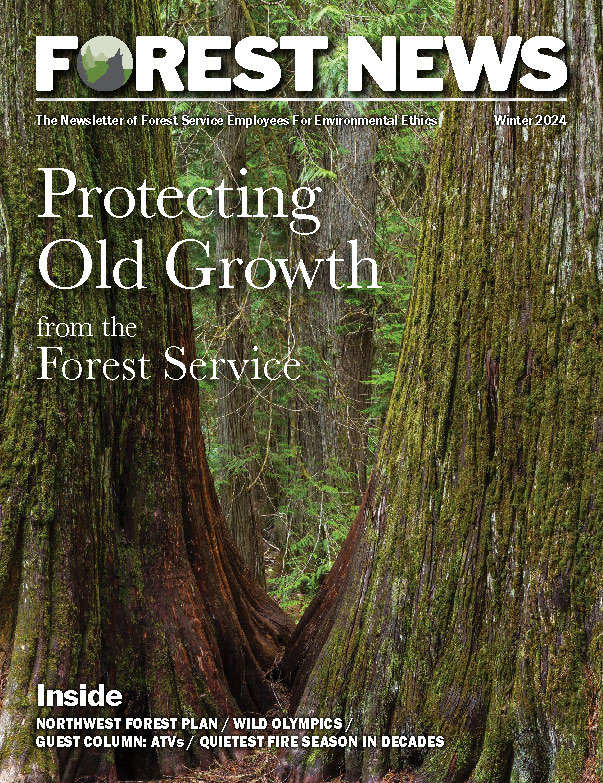

Even though these large trees are clearly not dead, they could be cut down as “hazard trees” under the proposed post-fire logging project in Willamette National Forest.

“Their plan is essentially blackmail,” said FSEEE Executive Director Andy Stahl. “They’re claiming the forest is this extremely dangerous, mortal hazard right now, which it isn’t. And then they’re saying, ‘Let us cut all these trees or we won’t allow you back on your own public lands.’”

“The risk of being hit by a falling tree is so small that it doesn’t come close to justifying these massive closures and it certainly doesn’t justify cutting thousands of trees critical to birthing the next generation of a healthy forest,” Andy said, pointing to testimony from Dr. Travis Heggie, former public risk management specialist for the National Park Service.

“Across all federal lands in the United States, 1% of fatalities suffered by the visiting public are caused by falling trees,” Heggie wrote, noting that falling while hiking or climbing is the leading cause of backcountry deaths (40%), following by avalanches (15%), drowning (10%) and heart attacks (10%).

“If the Forest Service were serious about public safety, they’d ban mountain climbing,” Andy said. “Risk is part of the outdoor experience,” and the same is true for burned forest. “Trees fall across forest roads all the time — there are roads festooned with trees that blew over in windstorms and they never close those roads or the forest.”

The injunction prevents the Forest Service from logging all trees except those “at risk of imminent failure” that are located near roads. The injunction also requires that any felled trees be left in the Forest, removing the Forest Service’s logging incentive since the trees cannot be sold for timber.

Andy expressed surprise that the Forest Service even tried to defend the project. “After taking the ‘hard look’ required by the National Environmental Policy Act, the Forest Service should come to its senses and realize that backcountry trees, whether dead or alive, are not a public safety hazard. To the contrary, these trees are the birth of our future old-growth forests.”

Judge McShane said the Ninth Circuit Court clearly laid out NEPA procedures for logging projects like this one in last year’s Environmental Protection Information Center (EPIC) v. Carlson ruling.

The Forest Service attempted to avoid the NEPA requirement by using a categorical exclusion for “repair and maintenance” of roads. Categorical exclusions allow projects that don’t have a significant effect on the environment to skip the requirement for either an environmental assessment or an environmental impact statement.

McShane said the Forest Service was wrong to apply the categorical exclusion and that the same question was settled in the EPIC case, in which the appeals court laid out clear guidelines for applying a categorical exclusion to logging projects.

“The project at issue … dwarfs the project at issue in EPIC,” reads McShane’s order. “The project in EPIC covered 180 miles of roads. This project covers 404 miles of roads. The EPIC project applied to 4,700 acres. Even the most conservative estimate of the project doubles the applicable acreage.”

The order also notes the commercial logging proposed for the project “will almost certainly have more than a minimal impact on the environment. … The commercial logging allowed here does not remotely resemble grading or repaving roads, cleaning culverts or removing brush (without the use of herbicides) near roads.”

Cascadia Wildlands, Oregon Wild, and Willamette Riverkeeper also filed for a preliminary injunction, and the court consolidated that filing with our case.

Nick Cady, legal director for Cascadia Wildlands, told the Statesman Journal, the Forest Service has “authorized commercial logging extremely broadly across a huge area with limited oversight. … They’re rushing to get as many trees as possible in a way that could damage rivers, habitat and drinking water. And we’re talking about critical areas for the environment.”

A representative for the Forest Service declined to comment on the judge’s order.