Can the Forest Service Kick its 100-year Addiction to Logging?

President Biden was widely praised for Executive Order 14072, which ordered the first-ever national inventory of old-growth and mature forests on federal lands. Issued April 22, 2022 (Earth Day), the order emphasizes “Restoring and Conserving the Nation’s Forests, Including Mature and Old-Growth Forests” and states, “My Administration will manage forests on Federal lands, which include many mature and old-growth forests, to promote their continued health and resilience….”

The inventory was completed in the spring of 2023, and in December ’23, the administration’s Department of Agriculture announced a proposal “to amend all 128 forest land management plans to conserve and steward old-growth forest conditions on national forests and grasslands nationwide.”

The Ag Department press release asserts, “Healthy, climate-resilient old-growth forests store large amounts of carbon, increase biodiversity, reduce wildfire risks, enable subsistence and cultural uses, provide outdoor recreational opportunities and promote sustainable local economic development.”

Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said, “Old-growth forests are a vital part of our ecosystems and a special cultural resource. This proposed nationwide forest plan amendment — the first in the agency’s history — is an important step in conserving these national treasures…. Climate change is presenting new threats like historic droughts and catastrophic wildfire. This clear direction will help our old-growth forests thrive across our shared landscape.”

Recent Forest Service actions have not kept pace with administration policy. For example, the agency is poised to approve a long-term plan for the Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison (GMUG) national forests in Colorado. As currently written, that plan allows commercial logging on more than 772,000 acres of public lands, including mature and old-growth trees — a 66% increase from the current forest plan.

The GMUG plan has been all but finalized, with the deadline for objections having recently passed. Objection resolution meetings are being facilitated by the National Forest Foundation. In this arid, high-elevation ecosystem, these fire-resilient forests will require centuries to regain their old-growth qualities once they are logged.

As previously reported, the Custer-Gallatin National Forest recently approved the South Plateau Landscape Area Treatment Project, a 16,462-acre logging project along the western boundary of Yellowstone National Park:

- 5,531 acres of clear-cutting.

- 6,593 acres of commercial tree-cutting.

- 56 miles of road construction.

Predictably, the decision swiftly met with a lawsuit. Several environmental groups are challenging the proposal for its impact on protected wildlife while pointing out how the project conflicts with President Biden’s pledge to protect old-growth and mature forests.

Initiated by the Trump administration, the Fourmile Vegetation Project on the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest in northern Wisconsin is actively logging old-growth trees, mainly to supply pulp mills. Andy Olsen, senior policy advocate with the Environmental Law and Policy Center has stated, “While the Forest Service also speaks of the need to ‘recruit’ more old-growth trees and forests, it is proceeding to log just such trees and stands in the Fourmile project area.”

Timber industry trade groups like the Great Lakes Timber Association support the logging, even though, as Olsen points out, “There’s a glut right now of timber on the market. The Forest Service says that over 85% of these timber sales are to be used for pulp for paper products. And that market … is saturated, so there’s no market emergency, but we do have a climate emergency.” Like the South Plateau Project, the Fourmile Project threatens sensitive wildlife.

“It’s also the last habitat for the American marten and a host of other things that need those old, intact, moist moss- and fungus-filled forests,” Olsen said. “That’s not what remains after these logging practices, even the so-called selective logging.”

The marten holds a special significance as a Clan animal to Ojibwe tribes, and Biden’s executive order includes honoring Tribal cultural and subsistence practices. “The Ojibwe tribes are concerned about protection of the Clan animal and only mammal protected under Wisconsin’s endangered species laws, and that’s the American marten. … Their logging is actually, they admit, it’s going to reduce habitat for the marten, which has struggled to persist,” Olsen said.

While the Biden Administration can be applauded for promoting the preservation of mature and old-growth forests, these logging projects in Colorado, Montana and Wisconsin reveal significant cognitive dissonance between science demonstrating the importance of preserving old-growth forests (much of it done by Forest Service researchers) and ongoing approval of old-growth logging projects by Forest Service bureaucrats.

Just one month before the Biden administration announced the proposed nationwide forest plan amendments, a Forest Service briefing dismissed the threat from logging. “Wildfire, insect infestations and disease — not logging — are the greatest threats to the nation’s oldest forests,” officials said. They called for “a new policy” to embrace cutting of trees to help mature and old-growth forests better withstand wildfire, an approach that has been largely debunked by recent research, including the work of Dr. Tonia Schoennagel, an ecologist with the University of Colorado. As she has documented, less than 1% of forest health treatments even encounter a wildfire during their effective lifespan.

Timothey Ingalsbee, Ph.D., is a fire ecologist and former wildland fire fighter. As he has pointed out, the Forest Service began promoting logging for forest health only after the agency was forced to drastically reduce old-growth logging 30 years ago. “The big shift in forest management and fire management came right at the early 1990s,” Ingalsbee said. “At that time … they were clear-cutting old growth to the point of driving species extinct. So there were court-ordered legal restrictions of clear-cut logging, and just like that, the focus of the agencies kind of morphed. They charted out [forest-treatment] prescriptions that basically any tree made of wood was subject to being salvage logged or thinned as hazardous fuel.”

Dominick DellaSala, chief scientist with the Earth Island Institute’s Wild Heritage Project, responded to the Forest Service briefing by noting that less old growth has been lost in recent years because past logging “nearly liquidated the entire ecosystem.”

In spite of history, in spite of valid scientific research, and in spite of Biden’s executive order, the Forest Service continues to promote, approve, and carry out old-growth logging. Is this an example of arduous bureaucratic inertia preventing agency reform? Is it an agency so compromised by special interests that it will never willingly reform itself? Or perhaps it’s just politics as usual designed to deflect reform and obfuscate the truth?

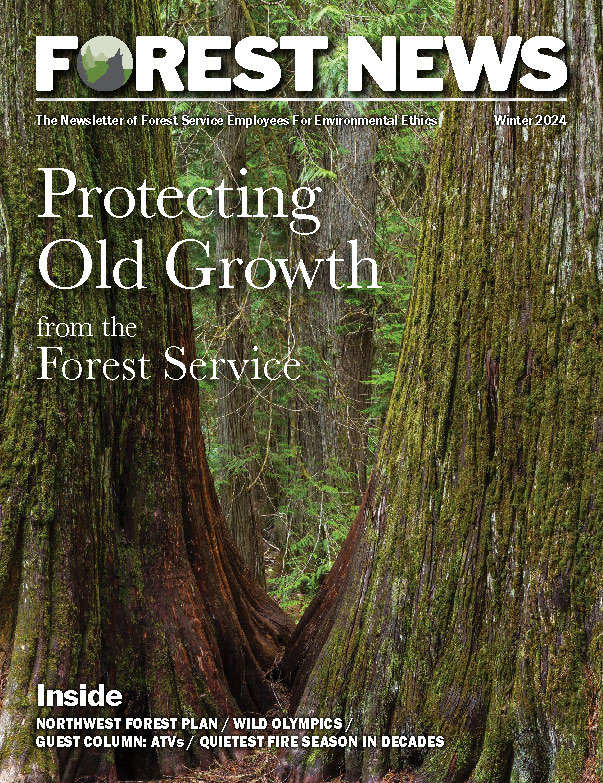

Photo: Old-growth western red cedar trees in Kootenai National Forest, Montana (photo by Don Paulson).