For the past several years, the managers of a reservoir in Oregon have let all of the water out for a week or so, so that the stream that feeds it flows freely.

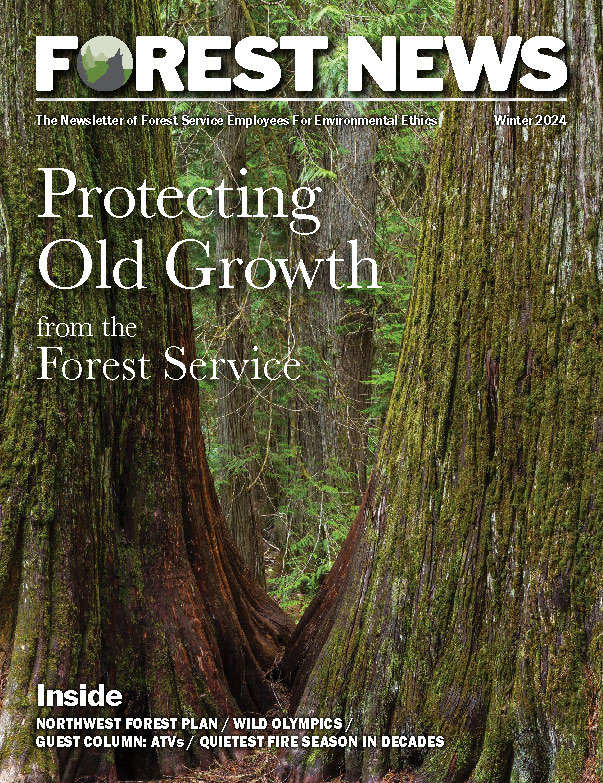

Managers let all the water out of Fall Creek Reservoir for about a week each year to help young salmon in their journey to the ocean. Photos by Christina Murphy, Oregon State University.

The result? A boost for native salmon and the elimination of invasive, warm-water species of fish. Those favorable results could have implications for how other reservoirs are managed in the Pacific Northwest.

A new study found that the practice helps juvenile Chinook salmon as they make their way to the Willamette and Columbia rivers and then out to sea. And the practice has eliminated invasive bass and crappie from Fall Creek Reservoir southeast of Eugene.

Researchers from Oregon State University, the Forest Service and the Corps of Engineers analyzed fish capture data from 2006 through 2017. The annual draining of the reservoir started halfway through that period.

“In 2012, we could capture 10 bass an hour,” said Christina Murphy, a recent Oregon State University doctoral graduate and the study’s lead author. “This went down each year. By the summer of 2015 we only caught one during all of our sampling and in 2016, we didn’t capture any.”

The drawdowns were conducted in the fall and winter, when the rivers downstream flow cold and fast. Those are challenging conditions for the warm-water fish.

“This type of research and monitoring before and after major changes in management of a reservoir is crucial for improving our ability to balance water availability while maintaining native species,” said Sherri Johnson, a research ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station.

Many of the region’s salmon-bearing streams and rivers have been dammed. The stagnant waters hinder young salmon’s ability to reach the ocean.

that seems predudise against people like like me who dont give a shit about slimey salmom or trout and would much rather catch some thing like bass that can out fight any salmon size for size. allso odfw puts trout in bodys of water that they cant survive in when the water gets to warm. what a waste.