Like the American chestnut, the American elm is threatened by an invasive species, but the future for the elms looks a bit brighter than the fate of the chestnuts. For elms the threat comes from Dutch Elm Disease, introduced in the 1930s, and researchers are making real progress with naturally disease-resistant trees.

Once common across eastern North America, American elms can still be found in forests, but because they soon succumb to Dutch Elm Disease, they tend to be much smaller and, therefore, no longer play an important ecological role. However, a small number of large American elm trees somehow remained healthy in the aftermath of the disease. Researchers are taking cuttings from these survivors, rooting the cuttings, and testing them for resistance.

Once enough of these clones are identified as resistant parent trees, they will be used to establish orchards for seed-stock production. The seeds will then supply nurseries that will grow seedlings to be planted in appropriate forests. In particular, resistant elm trees offer promise as a beneficial, indigenous option for ash-dominated floodplains hard hit by emerald ash borer. Since Dutch Elm Disease spreads through roots, providing some distance between the new elms will limit the potential spread of the disease.

The Forest Service Northern Research Station is leading the effort to identify disease-resistant elms with support from state, private, and Tribal forestry programs. The Chippewa, Superior, Chequamegon-Nicolet, Huron-Manistee and Ottawa national forests are identifying and collecting shoots from survivor elms and providing testing sites.

The Northern Research Station is creating clones of the upper Midwest survivor elms through softwood cuttings. In the coming years these clones will be planted and tested at sites in Oconto River Seed Orchard in Wisconsin, connected to Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest, and at a historic nursery site on the Huron-Manistee National Forests. The entire process takes about 15-20 years to complete.

“It is exciting to see us finally capturing clones of these magnificent trees. The progress we’ve made in the last two years would not have been possible without the cooperation of the many, many partners,” said Linda Haugen, plant pathologist with the State, Private, and Tribal Forestry Field Office in St. Paul, Minnesota. Haugen is coordinating capturing clones of survivor elms from northern cold-hardiness zones and the Upper Mississippi watershed.

“We need to develop populations of American elm that are locally adapted and genetically diverse. We hope to work with partners to establish similar programs throughout the range of the species,” said Cornelia “Leila” Pinchot, a Northern Research Station research ecologist who co-leads the project with Kathleen Knight.

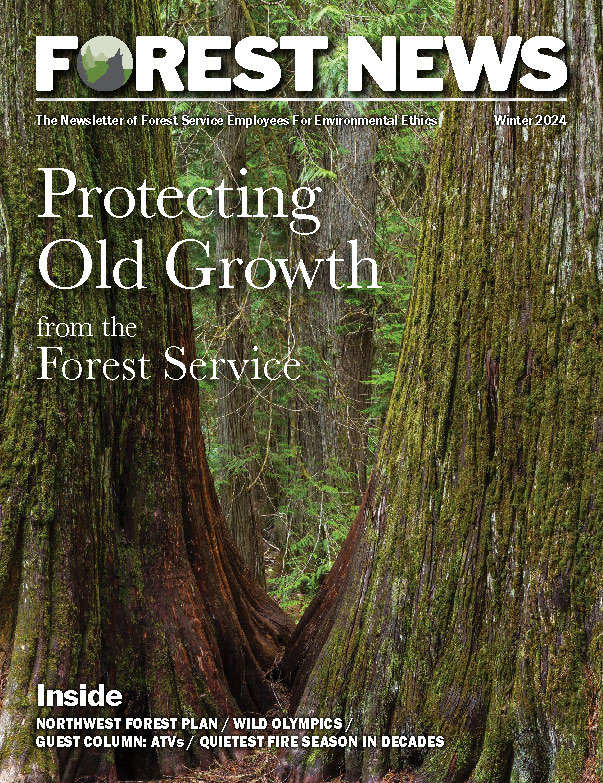

Featured Photo: A grove of American elm trees in New York City’s Central Park is likely one of the largest remaining.